MOVE ON TO NEXT PAGE

Back to Articles/Interviews | Back to Main Page

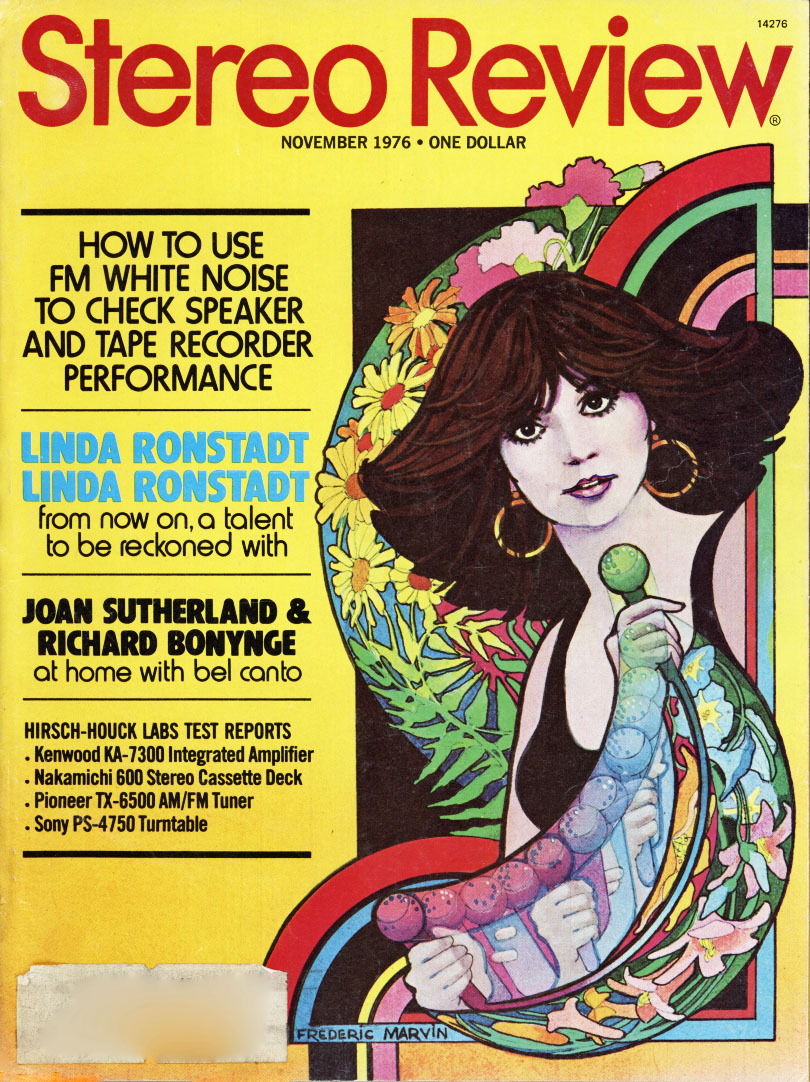

The Great Smokies Hilton sounded like CB radio talk for a haven for state cops. but it turned out to be a place where some of my assumptions about Linda Ronstadt were quietly dismantled. It was a fairly painless process- I'd do it again tomorrow- with two swimming pools and a golf course accenting the foreground of it and the Smoky Mountains serving as a backdrop. I caught up with her there, in Asheville, North Carolina, the town Thomas Wolfe couldn't go home again to, in the middle of a tour she and her band were making in their country-and-western-type Silver Eagle bus (but hers doesn't have a star's bedroom). I had listened to her records and seen her in concert a few times, most recently at Tanglewood where I had the exhilarating but scary sensation that everyone in the whole damned crowd had goosebumps, and I'd been exposed to the usual image-forming information and misinformation about her life style, bare feet, blue jeans, mussed-up hair, no fixed address, and that sort of thing. She was casual, was the impression this gave me, and the easy time she seemed to have when she sang reinforced it. The way she let her hips glide about when she slapped a tambourine during the instrumental break, the way she seemed to come out of left field to ornament a song with high notes, singing a bent line a fifth or even an octave above the score- it seemed so free and easy. So I assumed she ran mostly on her instincts and emotions and wasn't an easy prey for doubt and intellect and the way they circle one another. I remembered what a friend had said following the Tanglewood experience: "Boy, she can do it, and she knows she can do it." But here she was, approximately seven minutes after I'd met her and ten minutes before she had to go out there and do it, looking over the embroidery project she'd brought to the dressing room and telling me: "Spontaneity doesn't come easy for me. I have such terrible stage fright. I'm a slug, as far as my metabolism goes, a depressed person given to sitting around and worrying." People change, of course. Linda Ronstadt recently turned thirty, recently bought a house and fixed herself a Malibu Beach address, nowadays has a young woman travel with her as secretary and companion when she used to spend her off hours playing poker with the boys in the band, and nowadays wears a dress (and shoes) when she performs. She is even learning to cook. But the trouble about being spontaneous, she says, is nothing new. "You know the stuff they're finding out about the hemispheres of the brain, and the different kinds of control they exert?" she said. "Well, the intellectual side of mine gets the animal side by the throat and I have to fight to let it come out at all . . . . This is about the most fun I've had on a tour. I have to psych myself up for this kind of life, get manic and stay manic to get through it. It's like walking a tightrope over some kind of void- I'm out there and it's scary to be there, but I have to keep going or fall off." This probably reads more dramatic than it sounded when she said it. She is not afraid to talk about what she is afraid of, and does it calmly; it seems to fit the same pattern that has her performances seeming easy to us but not to her. She considers herself a late bloomer, "very late- I think of myself as still in the bud. I think it goes with being scared to death and with being a conservative person. I always had a basic intelligence I knew I could rely on. After that, I grew up so far from town, so far from civilization- my only friend was two years older than I was- that it gave me the world's most enormous inferiority complex. I went to a Catholic grade school which had the most ignorant, backward, intimidating order of nuns who shouldn't have been involved with anything except a mental hospital that they should have been patients of. They screwed me up real good. And then I left home early because I was just burning up to sing. I wanted to do music and I jumped into it when I was eighteen years old. I was a scared kid with an inferiority complex. "I knew I had good values and I knew I had a fairly keen judgment of human nature. My parents gave me that; they gave me a standard of what human beings should be. I never hung out with losers- I wasn't a groupie, never chased after success people. I never wanted to hang out with people who were self-destructive. I wanted to be with people who basically respected themselves. And my friends pulled me through. It was the only thing that enabled me to survive. Otherwise, I was comatose with depression most of the time. I was a chronically depressed child and I'm a depressed person." What she does about that, besides talk- which, understand, I think is a pretty good thing to do about it- is exercise. On the road, staying at places like the Great Smokies Hilton, she swims. "Get a change of chemistry in those cardiovascular passages," she said. "A lot of it probably is simply physiological." Another thing she is doing about it is, literally, growing up, "Turning thirty, I must say, is a relief," she said. "What a relief. It feels wonderful. I would not go through my twenties again for anything. I was miserable, confused, didn't know what was going on. This has been my big year of growing up. I fought it so hard because, remaining a child, I wouldn't have to accept any responsibility. I hated responsibility. I finally decided just to make the big commitment and grow up, and I love it. I'm finding I deal with things now on a much more honest basis. I'm more assertive, people don't take advantage of me as much as they used to- and people will always take advantage of you if you let them- and I have a much better sense of what I'm worth now. I mean as a person, not musically or success-wise, just what I'm worth as a person- which is bound to eventually reflect itself in the music, because music is only an extension of your soul, your psyche. "I spent most of my twenties getting in my own way," she said. "All that weird confusion and all that fecklessness and all that, 'Oh, my, we're such drowning victims. Aren't we tragic and romantic?' That's such a turn-off. Who wants a drowning victim? Much better to be a strong person and pull your own weight, be somebody who can help out if someone needs you, or be able to be helped." Linda spent her twenties more or less headquartered in Los Angeles and her first eighteen years at home, outside Tucson, Arizona, where her father still has what she calls "one of the world's great hardware stores." "He should have been a singer," she says. "He's got a great hardware store, but he's a greater singer." As a little tad, she was going into Mexican bars with her father, who'd often wind up singing with the local mariachi band. "And my sister was in love with Hank Williams when I was six and she was twelve," Linda said. "She had it so bad she would just moon over him continually, and we shared a room and I loved him too. I got him by osmosis. I was a radio freak when I was three. We lived so far away from town there was nothing to do except listen to the radio. It was 115 degrees outside and we didn't have much air conditioning. We had a cement floor in the living room and it was sort of cool and I remember I would spend all day with nothing on, lying on the floor with my head pressed up against the radio. I loved rock-and-roll, when that came along, just loved it." She doesn't consider herself a country singer- "I'm a pop singer"- although the town of Nashville sometimes seems to, perhaps because she sings more country songs than do most of her peers. One of the performers she currently admire most, and says she is learning a lot from, is Dolly Parton. "I use every root form I can get my hands on," she said, "or every one I can understand. Some root music is less accessible to me than others. Jazz is not very accessible to me, although there is some that I love and will listen to. Classical music obviously is not accessible to me to use much because it is technically out of bounds, but I listen to an enormous amount of classical music. The simpler root forms are available, like country and blues and gospel and Mexican music, especially. And the ones I tend to draw on most heavily are the ones I heard and learned and sang from the earliest time, country music and Mexican music and rock-and-roll. Jamaican music- now we had to really sit down and work at that." Jamaican music- particularly the political implications she sees in it- is one of her current passions. "Our whole band is reggae crazy," she said. "Musicians are always twenty-five, thirty years ahead of politicians, because musicians are the voices of the street. And the Third World is starting to happen. They're shambling along; their machinery is rusty. The language thing- no common language, all those African languages, dialects. Spanish and Portuguese- that's their biggest handicap. They've got nothing but music to unite them. And it'll happen. It will be a terrifyingly strong force, and it will be as bad as it is good, in a political sense, because it will draw in a lot of people who want an excuse for violence. The root core of the Rastas is peaceful; it says, 'I shot the sheriff but I swear it was in self-defense'- 'I'm not going to hurt you until you are killing me.' But, as it spreads to weaker individuals who have less of a commitment, they'll say, 'I shot you because maybe you were going to kill me.' I see them struggling with the beginnings of their material success. They're still singing for Shantytown, but the Wailers- well, Bob Marley's got a BMW now, and he's going on ahead and saying, 'Okay, now I've got this, and now what am I?' Trying immediately to put what happens in perspective." At the other pole from Jamaican music and its political implications is disco music and its political implications. Ronstadt has an analytical mind if I ever encountered one, and I sat back and enjoyed the workings of it as this thesis emerged: The Fifties, she said, amounted to a politically repressed era. Conservative times like that tend to bring out unnatural colors and exaggerated styles. "Even in ancient times," she said, "the Greeks and Romans, who were highly evolved politically, wore loose, flowing clothes and dressed naturally while the Elizabethans, who were repressed politically, dressed in those starched ruffles." The Sixties, she feels, were much more exciting, thanks largely to the Kennedys: "Whatever we find out later, upon re-examination, that they were worth, a new thing was happening." Styles got more natural. Exit the ducktail and the beehive, enter hair that was simply allowed to grow and hang down, among other things. "Now," she said, "we are in a politically repressed time and the styles reflect it. I mean, people are running around in outrageous-looking platform shoes and dying their hair green [enter David Bowie], and it's like Berlin before World War II. And the disco craze is right there. Disco music is horrible. It's like commercials, advertising, it's jingles. I like to see people dancing, but this is like subliminal, no-contact sex, anything to prevent getting really intimate with anybody, just keep it on that weird sort of surface, green-slime level." The media of course fasten on this and feed it as well as they feed on it, and Ronstadt doesn't seem to trust any media these days beyond some of the printed kind- she tries to read the Wall Street Journal every day- and says the heroes of the movies she and I grew up with, the strong, silent types, "all turned out to be defensive fools." "The movies have done it to us," she said. "The movies and TV have brainwashed us, made us believe all this stuff that was complete lies so they could take our money. I don't watch TV . . . don't even know what channels they have in L.A. I just can't turn that knob. I'm too impressionable to subject myself to that." She will, however, look up a movie that's supposed to deal authentically with Japanese culture, another of her strong interests now. She was (as I was) much impressed with Woman of the Dunes. She's been reading the novels and stories of the late Yukio Mishima- and (as I did) she avoided on principle the Anglicized butchery of the movie version of his The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea The non-Japanese books that have impressed her lately have included Dune, Frank Herbert's science fiction tale that has had what they called in the Sixties "great underground success." "'Fear is the mind killer' from Dune- that's one of my litanies," she said. "When I started to come of age musically, when my taste started to develop," she said, "hanging around Cambridge with the Kweskin Jug Band, I first became aware of that filter process, where you filter out all bad influences and you only listen to the best of the best of the best. It scared me so bad- I think it has to do with Puritanism somehow. It all started back there somewhere, I think, around Harvard, that double-think, that double-check, 'Is it hip, is it hip?' And, God, it squashed a lot of people's music. It's necessary to keep your standards up, but it's like the intellectual against the animal part of you; you've got to watch it or it can paralyze you. I kept saying in those days I didn't want to be a single, I wanted to be in a group. My confidence was devastated and redevastated . . . . When I first got to L.A., I could play C, G, and F on the guitar and there were all those hot guitar players and I just put the guitar away. Literally did not touch the guitar for eight years . . . . Fear is the enemy of us all." Fear may have served her, though, in a lefthanded way in that it kept her from being able to rush into fame and fortune too fast. She seems to have few illusions today about what those things mean, in part because she was able to get a good look at them before they enveloped her. "I was fortunate to arrive so slowly," she said. "I move like a little crab; I go sideways one step at a time and I cling to one rock until I'm almost drowning and then I move on to the next one. That's how I learned music, and I think my progress in my career was like that too. I was around the music business for ten years before I really made it big, and I knew exactly what it meant. I could not be fooled by it. "Mostly it means you get bothered a lot when you are out in public. It also means you've sort of priced yourself out of range for a relationship with most anybody, except for other people who are as famous as you are and are equally neurotic, and you don't want to have anything to do with them. That part can be impossible. It means you have to isolate yourself more and more. The more famous I get, the more I have to isolate myself. Everybody's got his hand out, everybody is intimidated by it, threatened by it, feels resentful. You get the worst out of people that way. "Try falling in love with a guitar player who isn't as famous as you are and see what happens. See how long he wants to stand up to that. And I'm out on the road all the time and they know what life on the road is like, and they aren't going to trust me for a minute. Or try falling in love with someone who's not involved in music and try to share it with him. Forget it. They just get jealous. I was going out with an actor for a while and I couldn't share what he was doing, and I got jealous." There's no, well, no whiningin the way Ronstadt says something like this; she says it straight-on, the way she talks about fear. She has learned something I think a lot of people need to learn about not being afraid of words. Beyond that, I had the impression that she deemed it wise to keep chipping away at her public image from the inside while welcoming whatever I could do in the way of knocking out chunks of it from the outside. She is one of the least guarded, least defensive persons, celebrated or not, I've talked with lately. Yet she knows as well as I do that the real her, if we could ever fairly represent it and give the people an unfettered look at it, would be misinterpreted, distorted, turned in effect into another image, for the eye of the beholder is never without prejudice. She also knows how slippery and subjective a concept "real" is, as in the "real Linda Ronstadt" or the real anything else- "reality," she says, "usually extends in all directions for about four feet"- but, my impression continues, she likes the Linda Ronstadt she knows well enough to try to help people see through the image. She doesn't mind your finding out she's scared up there on stage in spite of how confident she appears and how smoothly the show seems to go. And the metaphor she supplies for this is good enough for me: "You know how at Disneyland they have people wearing those Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck body masks? The kids go up to them and kick them, because the kids don't realize there's a person under there. That's what happens with people like me. The image is unreal, it goes out in pictures and on TV as just an image with no flesh and blood to it, and when people see me in so-called real life, they just see that. They're conditioned to think I'm not a real person." She's real, all right. The image I had of her was pleasant enough- nothing Mickey Mouse about it- but the real person under it is someone I'd like to introduce to my best friends. Thank you, Asheville. Sorry you were born too soon, Thomas Wolfe.