Thursday is talent night at the Palomino Club in North Hollywood. Young girl after young girl (and some

not so young) makes her way to the small stage. clutches the mike, takes a deep breath, closes her eyes

and sings: "Desperado," "Love Has No Pride," "Blue Bayou," "When Will I Be Loved," "You're No

Good." They all sing her songs precisely - every lick, each tiny inflection - just the way she does.

These girls have hooked their dreams onto her music. And it's likely the same thing is happening at

talent nights and hootenannies from Seattle to Boston.

Linda Ronstadt is probably the most successful woman singer of the Seventies. Cash Box named her the

top female pop singer of the decade; she may be the most popular ever. Her concerts sell out within hours

of being announced and she has had four records go platinum. To many, Ronstadt epitomizes not just the

Southern California sound but the Seventies as well. Her music, as the decade, is random and eclectic.

Ronstadt is an interpreter. Rarely does she write her own songs or play an instrument. She merely sings.

And her voice, technically soprano. seems capable of anything.

She has sung almost every form of music except, perhaps. hard-core disco - and succeeded.

She reaches way back for standards such as "Old Paint" and "I Never Will Marry" and sings them with

innocence. She lunges ahead into the risky territory of punk and knocks out a haunting version of Elvis

Costello's "Alison." She belts out love songs like "Loose Again" and "Down So Low" with the authority of

someone who has seen and done it all. She sings Mexican, Motown, reggae - and the girl can rock 'n' roll.

And when she sings a country tune such as "I Can't Help It (if I'm Still in Love with You)," there is no doubt

that Ronstadt has something for everyone.

She was born in Tucson, one of four children, in 1946. Her English-Dutch-German mother (whose father

invented such things as the electric stove, rubber ice trays, the grease gun) grew up in Michigan. Her

Mexican-English-German father, who runs a successful hardware store, is from an old Arizona ranching

family. At four, Ronstadt's father, who loved to sing, pronounced his daughter a soprano, and that was it.

From that moment, Linda wanted to be a singer. She became addicted to the radio, memorizing every song

she heard Music dominated her life.

She attended Catholic schools and her penchant for flouting tradition (a trait she picked up from her

maternal grandmother) surfaced early on. She teased the young priests, exasperated the nuns and wore

black pants under her white debutante dress when she made her formal bow to society. Ronstadt managed

to stick it out for one semester at the University of Arizona before hitting the road in 1964. Her worried

father slipped his daughter $30 and told her never to let anyone take her picture without her clothes -

probably the only advice Ronstadt has ever heeded.

Arriving in L.A., she hooked up with Bob Kimmel and Kenny Edwards and formed the Stone Poneys, which

was basically a folk/country band that played local gigs at places such as the Troubadour and the

Palomino. The group eventually signed with Capitol Records and released three albums. The band had one

hit, 'Different Drum." In 1969, Ronstadt struck out on her own and released her first solo album,

"Hand Sown, Home Grown." Her second album. "Silk Purse," was released in 1970 and included her first

hit, "Long, Long Time"; it also earned her her first Grammy nomination.

In 1971, she released her third solo album, "Linda Ronstadt," and formed a new band. which included

Glenn Frey and Don Henley, who later formed a band of their own, The Eagles. In 1973, "Don't Cry Now"'

was released. By that time, Ronstadt had a cult following, pulling her fans not only from the country ranks

but from pop and rock as well.

But it was in 1971, when she teamed up with Peter Asher, who became her manager and producer, that

Ronstadt took off. She released "Heart Like a Wheel." The single from that album, "You're No Good."

sprinted up the charts to number one. Her cover of Hank Williams' "I Can't Help It (if i'm Still in Love with

You)," also from "Heart Like a Wheel," won Ronstadt her first Grammy award for best female country vocal.

"Prisoner in Disguise" came next and was followed, in 1976, by "Hasten Down the Wind" and "Linda

Ronstadt's Greatest Hits." and Ronstadt won another Grammy, this time for best female pop vocal

performance. The Playboy Music Poll named her the top female singer in both pop and country categories.

There was no stopping her. The next year, she released "Simple Dreams," which some critics still call her

best work. The album produced five hit singles, including her all.time biggest single, "Blue Bayou." "Simple

Dreams" was also Ronstadt's best-selling album-over 3,500,000 copies in less than a year in the United

States alone. And PLAYBOY again named her the top female singer in both pop and country categories.

"Living in the U.S.A." hit the stores in 1978 with an initial shipment of more than 2,000,000 copies. That

album further demonstrated Ronstadt's versatility and growth. She sang the Hammerstein/ Romberg tune

"When I Grow Too Old to Dream," covered Smokey Robinson's "Ooo, Baby, Baby." Chuck Berry's "Back in

the U.S.A.," as well as Warren Zevon's "Mohammed's Radio" and Elvis Costello's "Alison." By that time,

she had appeared on the covers of many major periodicals, from Redbook to Rolling Stone to Time. Her

fans couldn't get enough information about her.

Ronstadt has broken new ground and remains unpredictable. One minute she appears barefoot, the next

she appears on roller skates (setting off a national craze), the next in Ralph Lauren boots. She wears a

white-silk dress to the Bottom Line and blue jeans to Nancy Kissinger's Carter Inauguration party. She is

rich (in 1978, she made an estimated $12,000,000). She is independent. She has talked openly of drugs,

sex, love, men. She is rumored to have bad romances with such men as J.D. Souther, Albert Brooks,

Mick Jagger, Steve Martin, Bill Murray and, most recently, California governor Jerry Brown.

PLAYBOY asked free-lance writer Jean Vallely to talk with Ronstadt about her music and her life.

Here is Vallely's report:

"I first met Linda Ronstadt in 1976 at Lucy's, a Mexican restaurant in L.A. when I interviewed her for a

Time cover story. Over the next four years, we became friends. To sit down with Ronstadt and actually

interview her again was fascinating. She has, quite simply, grown up. She is no longer the silly girl,

willing to say anything for effect. She no longer wants to appear flaky. Linda Ronstadt wants to be taken

seriously, as a woman and as an artist. To be sure, there is still a naughty streak that runs down her back

the size of the San Diego Freeway, but she has it under control. As she does her life. As she does her

music. I met with Ronstadt seven times, at her Malibu beach-front home.

"Her life is frenetic. One day the interview was interrupted as we all (Linda, her assistant, her bodyguard

and I) searched for the papers to the new Mercedes diesel station wagon that Linda had just bought - mostly

for her three dogs. Another time, she was in the midst of planning a $1000-a-couple benefit dinner for

Brown's Presidential bid. And through it all, she was in touch with her decorators, who were in the

process of remodeling her seven-bedroom mansion in Brentwood. All the interviews took place either in the

glass section of her house that juts out onto the sand, which she calls the teahouse, or at the kitchen table

(except for the two Sundays when Brown was there, working out on the deck, when we slipped upstairs to

her bedroom). We drank a lot of Tab. Those sessions were at once intense and enjoyable. Ronstadt is

generous, witty, articulate, smart and a whole lot of fun to be around ...and she sings like a dream."

PLAYBOY: You've just finished your first album in more than a year and a half. Was lack of inspiration the reason it took you so long?

RONSTADT: I was coasting on material that had evolved from a previous season. For a while there, the music was like a noise bludgeoning my eardrums, so I did a lot of traveling. I went to Europe with my mother. I cut my hair. I went to Africa with my boyfriend-

PLAYBOY: You mean Governor Jerry Brown?

RONSTADT: (Smiling, not missing a beat) And I didn't go to any of those places for musical reasons. Then I hurt my ankle and was in a cast. That made me stay home.

PLAYBOY: On the subject of Africa and your "Boyfriend" -

RONSTADT: I'm not going to talk about him.

PLAYBOY: We'll see how you feel about it a little later on. For now, what did you do while you were at home?

RONSTADT: The only thing that kept me there was my foot being in a cast. But It was the best thing that ever happened to me. I started watching a lot of televison. I tuned in right around the time of Jonestown. I thought, Is this what it's like all the time? I hadn't really seen the news broadcasters before - for example, Barbara Walters.

PLAYBOY: What did you think of Barbara Walters?

RONSTADT: Barbara Walters will forever be Gilda Radner to me. I saw Gilda before I saw Barbara Walters. I had never heard of Tom Snyder, either, until the first time I went to see Saturday Night Live and Danny Aykroyd was in his Tom Snyder getup. I asked him, "Why is your hair like that?" He said he was Tom Snyder. I asked, "Who's that?" I watched Danny for two years before I ever saw Tom Snyder, and now there is no way I can take Tom Snyder seriously.

PLAYBOY: Besides TV, what did you do with your time?

RONSTADT: A lot of reading, riding, playing with my dogs. But then I started getting really panicky. I thought there was something terribly wrong with me because I didn't have any new ideas for the album. I got real desperate.

PLAYBOY: What did you do?

RONSTADT: I visited some of my musician friends. I sat down with Wendy Waldman and we wrote a song. I saw (bass guitarist) Kenny Edwards and we stayed up all night singing. I went and saw Emmylou Harris. Then I went to every club in town and saw a lot of new stuff and went to concerts and saw people like Bette Midler. She is an awesome talent I think we've taken for granted. All the juices started flowing again. I realized that a lot of the problems with lack of inspiration - my own and others' - were because of our own cynicism. You know, the idea of ushering in a new fashion in the music business, like they do in clothes, just isn't a natural way for art to function.

PLAYBOY: You mean to force it is to fake it?

RONSTADT: Right. A lot of new stuff and talent is being taken for granted out there. I just hadn't been looking hard enough. So I really needed to have that rest. I got a chance to put myself in perspective with the rest of the world. I found out that music isn't the center of the universe. But, finally, it became boring to be away from the music.

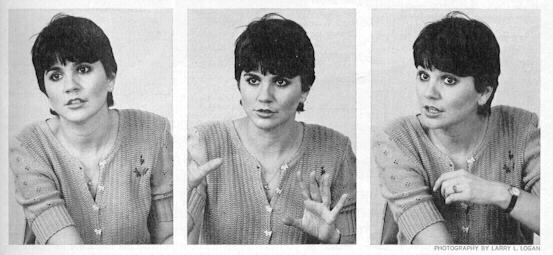

PLAYBOY: Did you cut your hair so short because you were bored?

RONSTADT: Kenny Edwards said he hadn't heard any music that made him want to change his hair style and I thought, Well, if I cut my hair, it might inspire me. What do you think?

PLAYBOY: It doesn't exactly go with your image. You look like a punk star.

RONSTADT: This (pulling at her inch-long hair) looks like what I feel like now. What seems to reflect me is a lot of change.

PLAYBOY: How have you been changing?

RONSTADT: I think I've kept the basic values that I got from my family and I'm glad for that. But the packaging is flexible. To me, there is something feminine about having a real boyish haircut - it's like a real feminine girl dressed in Army clothes - it accentuates the femininity, rather than diminishing it.

PLAYBOY: How does the new album Mad Love, reflect your recent experiences and changes?

RONSTADT: There is almost no overdubbing. This album doesn't follow what seems to be my prescribed pattern: a J.D. Souther song, a Lowell George song. a couple of oldies, kick in the ass and put it out there. In this album. almost all the songs are new. It's much more rock 'n' roll, more raw, more basic.

PLAYBOY: How did you get the new tunes?

RONSTADT: Elvis Costello, who I think is writing the best new stuff around, wrote three of the songs.

PLAYBOY: What did Costello think of your cover of his song Alison?

RONSTADT: I've never communicated with him directly, but I heard that someone asked him what he thought and he said he'd never heard it but that he'd be glad to get the money. So I sent him a message. "Send me some more songs, just keep thinking about the money." And he sent me the song Talking in the Dark, which has not been released here, and I love it. I also recorded Party Girl and Girl Talk.

PLAYBOY: You also have three songs from Mark Goldenberg. Who's he?

RONSTADT: Next to Elvis Costello, he's writing my favorite new rock 'n' roll. He's part of a group called the Cretones. He's great. I don't know how this album will sell. I'm sure I'll be attacked: "Linda's sold out, trying to be trendy, gotten away from her roots." But, well, can't worry about what the critics say.

PLAYBOY: Wait till they see your hair.

RONSTADT: (Grabbing her head with her hands) Oh. God!

PLAYBOY: Besides the New Wave stuff, what's going on musically these days?

RONSTADT: It is a strange time for all of us in the music business. The music is oddly lacking in different kinds of sensibilities. In the Sixties, there was such a variety; the delicate, romantic approach of Donovan, Motown, The Rolling Stones, the Beatles, all the country stuff. I like it when it's all messed up like that. Right now there is a whole lot of disco and it's just not the kind of music that inspires you or that gives you a personality to get involved with. The Seventies was a polished-up version of a lot of the things coming out of the Fifties and the Sixties. I think we refined them past their prime: like racing horses that have been overbred - they run fast but their bones break.

What interests me is that for the first time, American pop music doesn't seem to make a bow to black music - except reggae, which is Third World music. Pop music has always been largely based on American black music: jazz, blues, Gospel. And for a while, it was very much the thing for white musicians to be able to play with heavy black affectations; for instance, putting the rhythm emphasis way back behind the beat. If you could do that and keep the groove, that was a real hip thing to do, and now it is the opposite. The grooves are very rushed and fast and the emphasis seems to be very much on top of the beat. And the moves I see are very white. I saw the B-52s and their moves. Well, they look like someone in a Holiday Inn disco, sort of Ohio housewife dancing-very white.

PLAYBOY: What does that indicate, musically?

RONSTADT: For the most part, I think it's Whitey's death rattle. It's the end of the curve. The Third World music coming up will be the more dominant force after the year 2000. But the thing to remember is that there is still a lot of life in this curve - it's not expanding anymore, but it's still viable.

PLAYBOY: Before we get to the year 2000, what about the music just ahead - in the Eighties?

RONSTADT: The Eighties is a season of change, kind of like the Sixties just before rock 'n' roll exploded. A lot of us are kind of walking around wringing our hands and wondering what the music will be like. The most interesting things seem to be coming out of England again. At least my favorite things: Elvis Costello, Joe Jackson, Rockpile. L.A. looks like it has dried up as far as ideas are concerned. Right now there is a real vacuum. I keep turning the radio dial a lot.

PLAYBOY: Could it be that you're getting too old to rock 'n' roll?

RONSTADT: Well, every now and then, we clutch our hearts and wonder if we're getting so old we don't understand what is coming down. All of us worry that we are turning into old codgers. But that's silly. There's always the music.

PLAYBOY: How do you feel about disco?

RONSTADT: What I mainly believe is that the music should be very democratic. Disco is a good example. I don't really care for it myself and I hate to dance to it. I'd rather dance to Latin music or rock 'n' roll. Disco brings lots of people together but in a rather shallow way. I don't feel it should be wiped out, though, because there are a lot of people who like it and need to go out and dance to it. Every sensibility should be represented. One of the funniest things to me is that the East Coast has this snobbery against the West Coast: that we only manufacture shallow emotions and even shallower art. Yet it's the East Coast that gave us disco. They take for granted the Beach Boys and Randy Newman, Ry Cooder, great artists. The kids coming up are going. "Oh, the Seventies, all that music was trash, overproduced. too slick." and they are probably right. But we needed that for a while, just as we need their anger, too. I agree with them for the most part, but it doesn't mean that the music had no right to exist.

PLAYBOY: You sound defensive about the East Coast versus the West Coast. Is there a difference in the music?

RONSTADT: There is a real difference, and there should be. You go to the mountains and there is mountain music. You go to the plains and there is plains music. That's one of the things that make the music so interesting. But I am mystified by the vicious, violent feeling that the East Coast has against the West Coast music. I remember if it hadn't been for the Beach Boys, I wouldn't have been able to turn on my radio in high school. They are totally musical and totally a product of California. I just loved that. And I also know that if it hadn't been for the Drifters, my life would have been poorer. We had the Drifters singing Up on the Roof and Brian Wilson singing In My Room; two totally different ways of expressing exactly the same sentiment. I'm glad. It's all music.

PLAYBOY: So you like California?

RONSTADT: It's nice here. It's different from New York. I don't expect the same things. I don't expect a peach to taste like an apple. Sometimes I think we should all move to San Francisco. It's sure nice up there. Except it's too foggy.

PLAYBOY: Of course, people on the East Coast think that the only thing people from the West Coast talk about is the weather. And here you are, doing just that.

RONSTADT: God, why should we apologize for the weather? The weather is boring. for God's sake. I read this article in the sports section about the Dodgers. The writer was from The Boston Globe and it was, like, the meanest article I've ever seen in print. This guy was saying things like, "I'd like to see them shoveling snow. They always have perfect weather, perfect tans, perfect blue uniforms." If it got down to competing for weather hard-ships, the East Coast could have the hardest and we could have the most boring. It's so weird, I just don't think you have to undergo some horrible hardship just to be acceptable.

PLAYBOY: Enough about weather. Let's talk about you.

RONSTADT: Oh, Lord.

PLAYBOY: How do you feel about moving into your mid-30s?

RONSTADT: Being 33 is OK. It's 40 I'm worried about. I'm in pretty good shape these days. Exercise was the big thing, learning to exercise right. Everyone kept saying, "Linda, you've got to get some exercise," and I would think, Yeah. And then I would look through a magazine, you know, for the ten exercises to do before summer so you can fit into your bathing suit. And I would lie on the floor of my motel room and it was so boring and I never got any results, be-cause I didn't do it right.

PLAYBOY: How did you learn to do it right?

RONSTADT: It took some time. I went to a health club, but that was pretty confusing. Then I met this guy Max, who kept telling me I should lift weights, and I thought, I don't need muscles. Then I went to this health ranch where you couldn't eat and had to take seven-mile hikes up hills. God, I was miserable. But by the third day, I noticed that I was waking up feeling like I did when I was seven years old - clearheaded. Then I started running and it was the only cure for depression that I had ever encountered. I was so firmly into running, before I hurt my ankle, that I used to get in front of the television and run in place when I was on the road. The more I ran, the more I read about exercising and understanding exactly how the body works.

PLAYBOY: Weren't you afraid of building up large, masculine muscles?

RONSTADT: Women don't get big muscles like men. Their muscles just get firmer. I got real high just wanting to do it better. It was inspirational, having a regular exercise routine while I was with all those hard rock 'n' rollers - the gentlemen of the Great Indoors.

PLAYBOY: How did you pump iron on the road? Did you carry the weights with you?

RONSTADT: No, they were too heavy. We'd get to some place like Kansas City and we'd call a men's gym. It got to the point where I found there weren't any excuses. I didn't want to miss my daily calisthenics and weight lifting. And I began to realize how much of my life I fooled myself with excuses. It was a breakthrough. I needed to have a little victory and it carried over into other areas of my life.

PLAYBOY: How?

RONSTADT: Well, I always felt with my music that I was getting by by the seat of my pants. I didn't have a clear knowledge of how to apply myself. I had the same problems in school. I was at a loss with certain things like music theory. I couldn't learn it in school. I think it was explained in a confused way. But with the exercises, I realized that if I understood clearly, I could go on to the next step. And I've just turned the corner with some things about music theory that I've never been able to understand. I have a lot more confidence just in terms of my own ability to improve. And it really has made a difference in how I feel about everything I do. I learned how to work. I didn't learn how to work when I was a kid. It was too hot.

PLAYBOY: Too hot?

RONSTADT: It was too hot in Tucson, where we lived. So there I was, exercising, and suddenly I found I was doing better shows and I was happier. I almost hesitate to talk about it, because as soon as you do, it's written off as part of the California narcissistic movement. But, goddamn, it's a really good thing, to be able to think that when you are 45 or 55 or 65, you're not going to be crippled or diabetic or have a terrible heart condition. When you're disciplined, things happen. They do. They just do.

PLAYBOY: Do you feel you've become disciplined?

RONSTADT: Yeah, and I also learned about morality. Coming from a Catholic background, I was much more inclined to rebel against the idea of being good for moral reasons and stuff just because you were supposed to be. I don't like to do anything just because I'm supposed to. I always want to have reasons. That's the way I was with exercises. I found that weight training strengthened my will.

PLAYBOY: What does that have to do with morality?

RONSTADT: Well, see, if you adhere to some kind of moral code, whatever it is, it makes it a more efficient way to deal with people. One time I got caught being catty about someone and got busted for it. I realized that it made my position with that person and with the people who were witness to it weaker. So I decided that you have a contract with someone and if you're trying to break that contract, your case is weaker if you haven't lived up to all your parts. And every single day, we have little social contracts and the strengthening of my will just made it easier to deal with situations head on. So I am going to live up totally to my part of the bargain, whatever it is. If you play dirty tricks on people, it makes you weaker. And, in that sense, they've got a victim's kind of strength and I know a lot of people who maneuver and get into that position of being the victim because it gives them power. I hate that.

PLAYBOY: Sounds like a lesson you learned from your own experience.

RONSTADT: I've learned some pretty hard lessons along the way and sometimes I think the greatest sin is carelessness. When I was a child, we lived out in the country in a very dry area and there were scorpions and snakes and brush fires, all kinds of things, and you had to be careful. You didn't stomp on insects' nests or send dirt clods down the hill or throw matches around. And I think most people are careless, not just with other people but with things. It carries over to a piece of equipment I have in my house - not letting it rust or whatever, I'm beginning to have this theory that more and more, I should have only things I need. Too much clutter in my life makes me anxious. You know, you don't always get what you want, but sometimes you get what you need. Form follows function. It's just a much more efficient way to live. I'm real interested in efficiency.

PLAYBOY: Somehow, your image doesn't suggest a consuming interest in efficiency.

RONSTADT: Well, now my German background's coming out. I swear to God, I am a real Kraut at heart. I'm a firm believer in the appropriate application of a movement, of doing it exactly right. It's like reading your owner's manual. I went to Germany this past summer, thinking I would hate it. It was real nice. I like those Germans. So I decided that it was OK to let that part of my heredity assert itself, because the Mexican side of me had been running the show for such a long time. I love the Mexicans, but they're supposed to sing, sleep and eat and it had been dominating my whole personality. I began to think it was OK to be organized. And it started having a deeper effect. It changed my whole attitude toward a lot of things, including my music.

PLAYBOY: We'll follow up some more on your music, but we'd like to know why you feel you can't discuss your personal life - for example, your relationship with Jerry Brown, which is discussed publicly everywhere.

RONSTADT: I can't talk about him. I just can't. I don't feel it is fair to him or to me.

PLAYBOY: Why?

RONSTADT: (Jumping up from her chair, she rummages through some papers and returns with a copy of the April 1976 "Playboy Interview" with Jerry Brown and begins to quote aloud) "PLAYBOY: It would be interesting to know if it's possible to lead a normal social life as a young, bachelor governor. BROWN: I think it is. But not if you talk about it all the time."

PLAYBOY: That was a nice quote from him. But you used to talk about your private life very openly.

RONSTADT: Yeah, well, I'm just clenching my jaw a lot these days. It's one of the greatest lessons I've learned and the hardest. I did talk freely at the beginning. Some of it was compulsive laundry airing that was self indulgent and immature. But a lot of it was a genuine desire to communicate. I am not afraid. I don't have anything to hide. I have never done anything really horrible in my life. I am uncomfortable around people who are so carefully selective about what they allow to pop out.

PLAYBOY: Yet that's what you're doing now. What has caused this "denching of the jaw"?

RONSTADT: The press. I worry that the press is discouraging candor. It is encouraging people to be secretive about their lives. Just to sell copy, the press distorts and flat-out makes up things. I'm more quiet out of self-protection.

PLAYBOY: Are you claiming that all the stuff written about you in the past - the sex and drugs - was made up or distorted by the press?

RONSTADT: (Leaning toward the tape recorder) I've never taken drugs, not even an aspirin...

PLAYBOY: Come on, Linda.

RONSTADT: Look, if I did all the things that the newspapers said I did, I would have to be cloned. There are simply not enough hours in the day. Sure, the reports were exaggerated.

PLAYBOY: You mean you're not an authentic, hard-living rock 'n' roller?

RONSTADT: The real hard rock 'n' rollers are dead. The ones who survived paced themselves. But, yes, I am intense, and, yes I take chances, and, yes, I push it to the limit - but there is a limit. Look at someone like Rod Stewart. He's supposed to be the biggest drug taker, biggest chaser of women; I mean, look at that guy's face, his skin, his hair. If he were doing all those things he was supposed to be doing, his skin would be green, his hair would be falling out and he wouldn't be able to walk, let alone run around the stage the way he does. I've learned to pace myself. I just don't do things that are flat out stupid.

PLAYBOY: Pace yourself . . . you sound like someone in training.

RONSTADT: Well, basically, I'm interested in fitness and not confusion. I think we are moving into an era of polarization and it's going to be very violent and turbulent. I think the writing is on the wall and I don't want to be stumbling around with my senses altered. People like Ken Kesey and others were genuine social experimenters and I respect those people and they broke a lot of ground for us. I think reading about them is real good, but we don't have to take those little things that make us crazy. God, who wants to take acid? The thought is enough to make me break out in hives.... It's growing up, being more secure with yourself.

PLAYBOY: How do you find security?

RONSTADT: Security comes from knowing what you're doing. There was a time when the music just wasn't good enough. I'm doing my best work now. And being fit, in good shape, working out, makes you feel better than taking drugs. Those of us who managed to survive the Sixties are so grateful to be alive that the idea of taking things that, you know, will harm you just doesn't seem smart. Putting anything between me and reality has never done anything but make me feel less secure and more scared and awful. It's lies. I'm not comfortable with lies . . . though I still do tell a couple now and then.

PLAYBOY: We assume you won't during this interview. Why have you given so few interviews recently?

RONSTADT: Interviews, in a sense, steal your soul, your privacy. If I come out with an opinion about something, or a funny, snappy remark, I can't use it again. After it has gone into print, it has become useless, a cliché. But as far as the press in general is concerned, I was talking with (political writer) Ken Auletta about the fact that the Government has a complete set of checks and balances. The press has nobody to check its authority, to control it. And thank God there isn't. I would sooner see us go down in the worst kind of decadence and horrible corruption than see the press be censored; but if the press is unwilling to take responsibility for its actions, then it will cause its own demise. It's gotten to the point where I pick up a magazine and I just don't believe a quarter of what I read. I know how much stuff has been distorted about me. It even happens in places like The Wall Street Journal, my hero. I always thought it would be nice to be in there, but I didn't think it printed gossip or that it didn't check the facts. In some sense, I think that the unbridled cynicism of the press is the most dangerous thing in our society.

PLAYBOY: Is that what you saw on your African trip with your "boyfriend"?

RONSTADT: The African trip is a good example.

PLAYBOY: How did the trip come about?

RONSTADT: I asked if I could go. I had been on the road for a real long time and when I got home, the trip had already been planned and I wanted to go. Africa is a real interesting place and someplace I wouldn't go alone, because it's too strange to me. I never dreamed it would be OK. At first, I didn't even get an answer. Then I said, "Oh, come on, take me." He said yes. I didn't tell anyone, not even my mother. Then my publicist, Paul Wasserman, called and he said he kept hearing from newsmen that I was going to Africa and that he just wanted to warn me that the press was going to be on my tail. I said, "OK, forget it. I am not going, not if there is going to be trouble." That was the afternoon before we were supposed to go.

PLAYBOY: What made you change your mind?

RONSTADT: I thought, Why am I surrendering to these people? I am being threatened out of a good time. Then I thought, I can go and not have anything to do with the press. I am not going in an official capacity and I am not working. I am just going as a sight-seer and all I have to do is stay out of the way. If anybody asks me a question, I just don't have to answer. If anybody wants to take my picture, I'll just turn the other way. It's nobody's business what I am doing. Also, I was convinced that once we got there, we could ditch the reporters.

PLAYBOY: You obviously didn't do a very good job of ditching them.

RONSTADT: Well, first of all, I didn't expect the press to commandeer the entire first-class section of the plane. We went coach and the press was furious with us. They saw this as a clear-cut case of our being uncooperative. They kept coming back, trying to interview us. I wasn't talking. The stewardess kept trying to prevent them from taking our picture while we slept. God. If anybody took my picture on a plane, no matter who I was, I would consider that they had no right to do that. There was an actual struggle in the aisle between two photographers for a certain spot and someone dunked this nine-year-old kid on the head with a camera. The pilot had to come back and tell them to stay in their seats. The press were fools. It was an outrage that they would act like what we were doing was hostile to them. They accused us of a publicity stunt. It was the press who needed a publicity stunt, not us.

PLAYBOY: Sounds pretty melodramatic.

RONSTADT: It got worse. We had this very loose schedule and went to countries and cities we hadn't planned to go to. Then the press came up to us and said they would like us to go on a safari; that would make a good story and good pictures. We had no plans to go on a safari! One day we were in the desert, looking at a United Nations desertification project, and a baby camel walked by and it was just the cutest thing and I wanted desperately to pet it. I barely got one finger on it when all the cameras went popping and the camel ran away. The pictures went back to the States saying, "Ronstadt on safari in Kenya." I was no more on safari than I was on a rock-'n'-roll tour. The press constantly threatened us. They pounded on my hotel door and said, If you don't cooperate, we're going to give you a really hard time; we are going to follow you until we get the pictures we want. One day I was walking with a friend from my hotel to the car and a photographer jumped into the car. Now, if I were going from a concert hall to my car and a fan jumped into the car, I would be scared. I would think that person was trying to hurt me. My friend pushed this photographer out of the car and was scratched all the way down his arm. I would have felt totally within my rights, if someone jumped on me and clawed my arm, to turn around and relieve that person of his front teeth. But, see, if you do anything like that, the photographers scream at you and tell you that you're preventing them from doing their job.

PLAYBOY: The trip sounds like a disaster from your point of view.

RONSTADT: Actually, we had a great time. The plane ride, the incident in the desert and the photographer jumping in the car were the only encounters we had with the press. We did ditch them. The press managed to base three weeks' worth of news on three encounters in which I said not one word. They had so little to work with that they had to pad and fluff it with hopelessly implausible drivel; like we were getting married. I read one account about how I sulked all day in my room. You know what that was? I can't even remember how many hours we flew and all the waiting in the airports and stuff like that; so when we landed, I went to my room and slept for about 15 hours. I was sleeping, not sulking. I was in dreamland.

PLAYBOY: What was it like when you got home from Africa?

RONSTADT: For three weeks, I couldn't go out of my house. I was so embarrassed. There were so many people aware of what my face looked like. I couldn't walk down the street or into a restaurant without everyone staring and pointing. It is so dehumanizing, I got defensive and wouldn't talk to anyone, and then people said I was a snob. I don't know those people. I don't have to talk to strangers. I really understand why people want to hide and become recluses. It would be good for this society to be encouraged to be as open as possible, because when society is encouraged to be closed, then evil things develop in the dark; horrible little stunted things grow out of darkness. That's what the press is encouraging.

PLAYBOY: Would you rather not be famous?

RONSTADT: Well, it's hard to go to the market and buy chicken, but I'm glad people think I'm cool and I understand a little of what the fame thing does to you. Take the Eagles, who have been my friends through the years. If I don't see them for six months or so, I begin to think of them as stars. I'll think about calling them, and then I'll think, Oh, they're so busy, they're such big stars, they don't want to hear from me. I called Don Henley the other day and he was so sweet. But we had this very businesslike conversation; I hadn't talked to him in months and I was kind of nervous and he responded in a businesslike way. He called back and he said, "What was that all about? How have you been?" And he came over with a bag of figs and we had a great time. I mean, the last people who should be falling for one another's press hypes are us.

PLAYBOY: Does fame make social situations easier?

RONSTADT: I used to think it would make it a little easier when I went to a party, because I wouldn't have to impress anybody, people would just sort of automatically be impressed. And there was a period when I was moderately successful when I could just walk into a party and have a good time. But I went to a party the other night and I was more embarrassed than when I was in high school - a nobody and socially screwed up. Everybody was staring at me and saying, "There's Linda Ronstadt," and people immediately took sides, for me or against me. And the sensitive people have enough respect for themselves not to be swayed by my presence and they just usually hang back. You mostly don't get to meet the nice people.

PLAYBOY: Would dark glasses help?

RONSTADT: I realized what protection dark glasses are when I did this concert once. I close my eyes when I sing. I get scared when I open them and see all the people. But this concert was outdoors, 105 degrees and the sun was blaring and I had to wear dark sunglasses, and I kept my eyes open through the whole thing and I realized how much I close my eyes as a device because it's unnatural to have thousands of people staring at you. It's embarrassing.

PLAYBOY: If you won't talk about Jerry Brown directly, how about men in general?

RONSTADT: Great. I adore men. God. I love to flirt. Flirting isn't necessarily based on offering yourself in a sexual way. I hope I'm flirting when I'm 80. I just love real vibrant older women who don't deny their sexuality but who also don't try to act like it should assume a place in their lives that is inappropriate to their age. That's a fine line to walk.

PLAYBOY: What do you mean?

RONSTADT: This may sound terribly racist, and I don't mean it to, but I have noticed that black women, when they're older and if they tend to get heavy, still dance and sing with the same sense of abandonment that they had when they were young and thin. She knows she's hot. A white woman, in the same situation, if she got up to dance at all, which she probably wouldn't, is so self-conscious. There is a certain amount of sexual posturing that goes on between human beings. It can go on between two women, a man and a woman, two men. Boy, men sure do strut for each other. I think that the desire to relate to people in a sexual way is a natural thing.

PLAYBOY: Do you think of yourself as a professional at the art of flirting?

RONSTADT: I'm not bad. But the pro is Dolly Parton. She is able to flirt and be very overt and sexual in a way that challenges. but there is no cruelty in it or unkindness. She relates to children, men, women. all in the same tone. She broadcasts her femininity all the time and is consistent. I get suspicious of someone who changes drastically in the way he treats men and women. But if there is someone around to spark you sexually, it really does make you get up and do your best. I love that. And it doesn't have to be an ongoing sexual thing. If there is someone I like to flirt with around before I go onstage, my shows are always better. It's a good way of priming the pump.

PLAYBOY: When did all this flirting start?

RONSTADT: I have always been boy crazy . . . since the first grade. Maybe it was because there weren't many boys around. I really wanted them to like me and I was really concerned that they might not think I was attractive. In high school. I really believed that the boys might not like me unless they were physically attracted to me: that I couldn't keep their attention unless they were on the receiving end of that sexual dynamic and that if I didn't set up that sexual tension, they would walk away from me. And I was often afraid to let go of that and rely on the nuts and bolts of the friendship. So I think I sometimes overloaded that end of it.

PLAYBOY: Any regrets?

RONSTADT: I regret none of it. I loved some of it, hated some of it. but it was all part of the experience.

PLAYBOY: When you were starting out, did you expect to become as big as you have?

RONSTADT: When I came to LA. in 1964, I kind of looked around and thought that maybe the kind of career Judy Collins had was perfect. She was quietly putting out things that seemed tasteful and sold respectably. That was the kind of career I wanted: a career where you earned a nice living, your records sold well, you had the respect of other musicians and did things in good taste. I never tried to become the next big thing. It seemed that was something to be guarded against at all costs.

PLAYBOY: What happened?

RONSTADT: It's unnatural not to reach out, not to try to progress. What are you going to do? Start walking sideways? So there is no way to control those things. I was going along, making country-rock albums, experimenting. I felt I was somewhat of a pioneer in that area. I felt like I was throwing some new ideas onto the pile. My records were selling OK. I thought I had arrived. That was before Heart Like A Wheel. I had no idea I was destined to be more.

PLAYBOY: Was Heart Like a Wheel the turning point in your career?

RONSTADT: Yes. In the early Seventies, I was in a rut. I didn't know how to get out of it. I was on this plateau that seemed endless. I was so numb. I could hardly see or feel. In fact, it all feels now like a murky dream.

PLAYBOY: What caused the rut?

RONSTADT: Years and years on the road. I was punchy. In fact, the fluorescent lights in certain kinds of dressing rooms make me crazy. (Laughs) If anyone ever wants to brainwash me, if I'm a hostage and they put a fluorescent light on me, I'll become a Communist, anything, you name it. God. I hated those years. I tried to stay unconscious the whole time.

PLAYBOY: How did you lift yourself out of that comatose state?

RONSTADT: It was thanks to my relationship with Peter Asher.

PLAYBOY: How did that happen?

RONSTADT: I had decided I wanted this person from Nashville because I wanted to explore the country area some more. But I became friends with Peter. We hung out a lot. But he was managing Kate Taylor at the time and he felt that if he took on another girl singer in the same market, it wouldn't be fair to either one of us. Then I ran into Kate and she said she was going to stay home then. so why didn't I call Peter?

PLAYBOY: Why did the combination work so well?

RONSTADT: Peter has a very rounded musical background, like I do. He listens to everything. His taste is eclectic. But there is a thread of taste and quality that runs through everything he does and because of the consistency of the quality, I was able to really trust him. And because I trust him, he is a good sounding board for all the things I want to do.

PLAYBOY: There are those who say he controls you.

RONSTADT: I'm more secure musically now than I was, but I never wanted to become the boss lady. As I see it, it is always a team situation involving me, Peter and the band. I never want to feel like the boss. Peter doesn't want to feel like the boss. We jointly make the final decision about everything. Neither of us wants to do the whole job. We're too lazy.

PLAYBOY: Do you do everything Peter tells you to do?

RONSTADT: No. If we disagree on something. I really re-examine it and if I still think I'm right, I go ahead. I remember Blue Bayou - Peter was afraid it wouldn't be a hit. He said we should shop around for some insurance. I said, "OK, get the insurance." But I knew it was a hit and it was the biggest single I've ever had . Sometimes he is real wild about stuff and I say, ''Oh, no. That will never go."

PLAYBOY: Do your instincts generally prove to be right on the mark?

RONSTADT: There are those times when I am just plain sure, when I have that incredible right feeling; and when I have that feeling about a song and I put it on a record, it usually doesn't miss. But sometmes it works the opposite way.

PLAYBOY: For example?

RONSTADT: I didn't think I sang Different Drum or Heat Wave particularly well. I was really on the fence about those two, but the public certainly didn't respond the same way. I'm sure the songs on Mad Love are the right songs for me.

PLAYBOY: Is there a point of diminishing returns in working with someone as closely and for as long as you've worked with Asher.

RONSTADT: Peter, Val (Garay the engineer) and I pretty much felt we exhausted the possibilities within the confines of the style in which we had made records. I wanted to change. And I wondered if I should change producer and engineer for the new album. When I approached Peter about this, he had to talk to me wearing his manager's hat. He never jealously guarded his role as producer. He encouraged me to think freely of all the possibilities. Then I realized that the desire to stretch was on all our minds and it seemed to me that to take that step as a team, I would wind up with a much more solid and authentic version of of what I wanted. It was the best decision I'd ever made.

PLAYBOY: You feel the changes were positive?

RONSTADT: Yeah. The stretch seems completely natural. A lot of the avant-garde stuff isn't the standard form - verse, chorus, verse, chorus. Groups like the Talking Heads are doing real interesting stuff, but for me, I still need a song that works in a verse, chorus, verse, chorus format - like the stuff the Cretones and Elvis Costello do. To adopt a new musical style just for the sake of it is like putting on a chicken suit - it looks ridiculous. At the same time, I wanted to change, yet the the thoughts of changing producer and engineer made me sweaty under the armpits. We had worked together for so long. But we all wanted to flex our musical muscles on this one. It feels good.

PLAYBOY: Do you feel you are at the height of your career?

RONSTADT: I certainley don't feel that I have accomplished what I would like to accomplish artistically. I feel like I am only beginning to learn how to sing in a lot of ways. So, to me, it is like a beginning. How the public views it may be totally different. I am certain I am doing my best work. But there are people I watch when I am stuck.

PLAYBOY: Such as?

RONSTADT: Warren Zevon and Neil Young; those guys are amazing. Randy Newman is one of the main ones. He has his hand on the tow bar. I don't know about that guy. I suspect he watches a lot of television and reads a lot of periodicals and it all seeps into his brain like a giant computer. His lyrics are subliminal way of predicting the future. I watch his lyrics and when I see a shift, I know it's going to show up later on, not just in music but in society. And his new album is pretty alarming, in the sense that violent polarization is dominant.

PLAYBOY: Then do you think the Eighties will be a decade of violence?

RONSTADT: Well, look at that new group The Dead Boys. And that group Police. They have that song, "You'll be sorry when I'm dead / and all that guilt is on your head / and I guess you'll call it suicide." And I hear a lot about war. The Talking Heads have a song, In Time of War, with a line that goes, "This ain't no disco / this ain't no GBGB's / don't have time for that now." It's like the era of self has to end in war, because war is the only thing that's great enough to distract one from one's self. That's pretty horrible. Neil Young has that song Powder Finger. It's just starting to creep into the lyrics enough to make me sit up and take notice. There is definitely violence in the new stuff. I'm looking around at the new music and searhing for a helmet or a hard hat.

PLAYBOY: Let's talk about something lighter. What's your ideal evening?

RONSTADT: (Laughing) Sitting up in bed with my boyfriend and reading a book.

PLAYBOY: On the subject of bed and boyfriend -

RONSTADT: Oh, no, you don't. Why don't we talk about my ideal dinner party instead?

PLAYBOY: What would you serve?

RONSTADT: Turkey. It would have to be turkey, because that's all I can cook.

PLAYBOY: Whom would you invite?

RONSTADT: Leo Tolstoy, Mozart -

PLAYBOY: Oh?

RONSTADT: Yeah, but I'd only invite Tolstoy when he was in the kindest and most earnest part of his life. I read a lot of Mozart's letters and he seemed like a real nice guy.

PLAYBOY: Don't stop. Who else?

RONSTADT: Bergman . . . and then I would have Fellini, because they're each other's favorite directors and they'd have something to talk about. I wonder if Mozart and Fellini would have anything to talk about. Oh, and I would invite Liv Ullmann. She's my favorite actress. I met her once and, oh, God. I was sure I had on all the right clothes, a nice new suit, a hat I bought in a secondhand store - I always have to throw something weird into an outfit - and my make-up was perfect. I wanted to look special. And when I walked into her dressing room, I just knew my nose was shining so bad you could see it four blocks away and I was sweating and my make-up looked caked on and greasy and my hat looked ridiculous and I'm sure my suit was wrinkled. I stammered like an idiot. I'm sure she thought I was a complete goon.

PLAYBOY: You can explain all that to her at your dinner.

RONSTADT: I'll have Tolstoy explain; he'd do it much better.

PLAYBOY: What about inviting someone like Mick Jagger?

RONSTADT: Well, that would be interesting, but Mick would have to be on his best behavior. I wonder what Mick would say to Mozart? The dinner needs some singers. Well, I'll be the singer . . . don't need any competition. Oh. we'd have to have Albert Brooks. Albert's so funny and bright and he can make every one laugh. Then I'd invite Peter Asher and Jerry -

PLAYBOY: Jerry who?

RONSTADT:(Making a face) And then I'd make Peter and Jerry stay after everyone had gone and we'd talk about them. Peter always has the best things to say about people and Jerry has a completely opposite viewpoint, but real accurate . . . I wonder if Mozart likes turkey?

PLAYBOY: In real life, you have a lot of movie people over for dinner; are the rumors true that you'll soon become a movie star?

RONSTADT: That's like asking someone who's a plumber if he's going to become an electrician. I've worked all this time to learn how to become a singer and really strived to get good at it. Why should I try to do something else that I have no idea how to do? Which is not to say I'd never make a movie, but at this time, I can't see making a career change.

PLAYBOY: Do you go to lots of movies?

RONSTADT: I used to have a boyfriend who loved to go to the movies and now I have a boyfriend who doesn't have any time to go to the movies.

PLAYBOY: What is taking up so much of your boyfriend's time?

RONSTADT: Three guesses.

PLAYBOY: What's your favorite movie?

RONSTADT: I have three, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, The Seventh Seal and Scenes from a Marriage. Those movies tell life to me.

PLAYBOY: OK, back to more serious topics. Do you think you've made an impact as an original artist?

RONSTADT: I remember not long ago standing in the dressing room at the Universal Amphitheater, talking to some Warner Bros. record guy who said he was looking for a girl singer like me. It made me feel so funny. I had become a trend, like when the English were a trend. I was this female who could sell records, and suddenly, female artists became cool. I hear girls singing with the same kind of inflections that I do. I remember so many times sitting down with a record when I was young, trying to copy every tiny inflection of a girl singer. But there are better girl singers than me - Bonnie Raitt, for example. I don't think I've made the kind of impact that changes the face of music like, say, The Rolling Stones or the Beatles. And not in terms of writing the book on singing style. At some point, all girl singers have to curtsy to Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday. I brought together a lot of kinds of straight threads of music and put them in a little fabric that has an interesting design. I had commercial success and opened the door for girl singers.

PLAYBOY: Are you afraid of being blown out of the water?

RONSTADT: There will be some female to come along who will blow me out of the water and when she does, you know what I'm gonna do? (Grins, makes a fierce face) I'm going to watch her real close, find out where all her hot licks are and steal them. You know, Bonnie Raitt was the first girl to get up onstage and play the guitar and have the guys say, "Hey, she doesn't play like a girl." And she didn't try to copy the opposite attitude and play real macho. Bonnie simply plays her instrument as if it were an extension of her arm and she succeeds gloriously. And I think there is a whole wave of little girls out there who not only will be able to play that guitar but will sing and have a real impact.

PLAYBOY: Anyone on the horizon?

RONSTADT: One night, I was really desperate for some inspiration. I went with a bunch of people in the music business to see Louise Goffin (Carole King's 20-year-old daughter). We were all holding our breath. I knew she was good, I had heard some of her stuff in the studio, but none of us were sure how we felt about that. Just before the curtain went up, I thought, Do I want her to come out and fall flat on her face? If she did, I could go "Phew!" But then I thought, If she blows me away, I will have some inspiration and that will be good. I decided I wanted her to be great.

PLAYBOY: Was she?

RONSTADT: She was wonderful. She was exciting and she had so much confidence. You know, all we female singers in the Seventies knew was that we were these independent people going around the country, earning our own living, and that we represented something because all these articles were written about us. But we didn't know how to arm ourselves. Our defenses were put on in a clumsy fashion. Louise came out the quintessential Eighties woman. She wore her defenses like enameled veneer. It was beautiful. She understood exactly who she was and how to protect herself. She had done her homework. She knew how to move around. She knew her craft thoroughly. Stevie Nicks leaned over to me and whispered. "Gee, do you think we still can get a job singing backup for Joe Cocker?" We were the graduated class.

PLAYBOY: You have a reputation of helping women singers such as Karla Bonoff, Nicolette Larsen, the Roches -

RONSTADT: It's not a deliberate attempt on my part. We're all friends. I was the first one visible. We've been helping one another out for a long time. I've drawn on a lot of their stuff.

PLAYBOY: Are you ever secretly afraid one of them will get bigger than you?

RONSTADT: To me, a new person coming up is good. Take Emmy (Emmylou Harris) for example. When I first heard Emmy sing, I wanted everybody to hear her. I love Emmy. She's the most inspiring singer to me, bar none. I would rather sing with Emmy than with anybody else. She can make me feel the music and the ideas of a song like nobody. I can't imagine Emmy not being successful, because that might mean that I can't sing with her so much. I mean, it's in my best interests for Emmy to be successful and for people to hear her, because she brings up the general standards of the music.

PLAYBOY: When did you meet Emmylou?

RONSTADT: I was in Houston on tour with Neil Young and we had a night off and Emmy was playing with Graham Parker. I kept hearing about her and that she was the only one doing what I was doing. At that point, we were struggling to get record companies to listen to us sing Hank Williams. I saw Emmy and I died. Here was someone doing what I was doing, only, in my opinion, better. But hearing her finally outweighed the pain of being outdone and I just thought, Well, here's the level and I'd better get up there; I'd better fight for it. I sat down with Emmy and sang and I learned a hell of a lot about singing from her and I still do.

PLAYBOY: Whatever happened to the album you and Emmylou and Dolly were making?

RONSTADT: We're still trying. It was a ludicrous situation. We were trying to make an album in ten days. We three grownups should have known better than to put ourselves in a pressure cooker that way. We just wanted to do it so badly and thought that was our only chance.

PLAYBOY: Are the rumors true about the three of you fighting?

RONSTADT: No. And the potential for hideous and bitchy behavior and accusations was enormous. At the very beginning, we made a solemn pact that at any time our friendship was hurt, we would end the project. Friendship first. And when I think of the kinds of things that could have happened, it blows my hair. The thing is that Dolly - God, there is not one trace of malice in her - has such a keen understanding of what motivates people that there was never a trace of bitchiness. Basically, what I learned was that I wanted to be on the team with Dolly and Emmy. singing with them is a predous experience. It was like musical nirvana. I learned a lot about music and about morality, and Dolly was responsible for that.

PLAYBOY: Some of your most beautiful songs are with them.

RONSTADT: There are people who act like catalysts for me. They make me do things I can't do on my own. When I sing with Emmy, she can make my voice go into a corner I can't reach by myself. And as for Dolly, when I sang I Never Will Marry in the studio, it just didn't have any magic. But all of a sudden, when Dolly started singing with me, wow!

PLAYBOY: Anyone else spark you like that?

RONSTADT: Sometimes I need an interpreter. Waddy (Watchtel) taught me how to sing Tumbling Dice. He really understands The Rolling Stones better than anyone except Keith Richards. And if you want to know about the Beatles, you go to Andrew Gold. If you want to know about Roy Orbison, you ask J. D. Souther. If you want to know about Neil Young, you ask Dan Dugmore. And if you want to know who to ask, you ask me. I'm the expert on who to ask. There are some people who work well all by themselves. Some of those Swedish fiddlers who sit in front of the mountains and just emote this passion are wonderful. But I live in a complex society and there are a lot of people around and I just need somebody to come in and put the other parts of the puzzle together for me.

PLAYBOY: You know, of course, that there are people who think of you as the sex symbol of the rock business.

RONSTADT: (Laughing and tugging at her Arizona State T-shirt and baggy jeans) Sex symbol! Look at me. I am not a great beauty, that's for sure. I didn't set out to become a sex symbol. I set out to be a singer. I think of myself as a sexual being. It's an important part of my life. I've never tried to keep sexuality out of my personality or my singing. It's fun that people think I'm sexy.

PLAYBOY: Do you have groupies?

RONSTADT: Well, guys come up after the show and want me to kiss them.

PLAYBOY: Do you?

RONSTADT: I don't really like to kiss strangers. I couldn't imagine 17 juicy, wet kisses from 17 strangers. It's unsanitary. You'd have to go home and get your teeth cleaned.

PLAYBOY: So guys don't knock down your hotel door?

RONSTADT: I think men are more naturally inclined to promiscuity than women. I don't know if it's biological or what, but men are able to depersonalize sex a lot more than women and still remain nice persons. The guys I know on the road are holy terrors, but I love them.

PLAYBOY: You mean you don't fool around on the road?

RONSTADT: I don't like to go to bed with strangers. (Laughing) I like to know what kinds of books they read. I wouldn't be interested in someone who had a groupie mentality.

PLAYBOY: You have been linked with many famous, rich, successful men through the years.

RONSTADT: Well, it would be very odd if it turned out that I had had a long relationship with a dentist. I mean, I meet famous people. I tend to have relationships with people I admire, who tend to be successful. I mean, who are you going to get a crush on? Somebody you don't admire? Why would you want to go out with a loser? What would you talk about? How I lost my job last week? But I have lots of friends who are successful and not famous. It's just that when I go out with someone else who is famous, it gets written about - makes better reading.

PLAYBOY: When you meet a man you admire, what's the next step?

RONSTADT: I have to get chased a whole lot. I need a lot of convincing, especially if he's famous. I don't want it to seem that I'm standing in line. I have to be convinced he is more interested in me than any of the other women interested in him. I have to know that I'm the exceptional one.

PLAYBOY: How long do those relation-ships usually last?

RONSTADT: I go out with a guy either for a night or for a year. I rarely have boyfriends for less than a year. Some just move over to friendships.

PLAYBOY: Is it hard to keep former lovers for friends?

RONSTADT: You have to explain what the nature of the relationship is, going in. Are we going steady? If you don't promise something that you don't have any intention of delivering, you can move on and not leave bitterness behind. I never felt obligated to be physically faithful to anybody or to be in any way emotionally entwined with just one man. I have never made that promise. I have never had a ring around my neck or an engagement ring or a wedding ring on my finger. If I did make that promise. I suppose I would be mad if I didn't honor it. So I enjoy and let the other person enjoy, and some of that's sexual.

PLAYBOY: Where does love fit in?

RONSTADT: Being in love is the best way to excite the feelings of sexuality. But you can't fall in love with everybody you are hugely, physically attracted to. I think you fall in love once, maybe twice. If you are dumb enough to screw it up the first time or unfortunate enough to lose it and if you're lucky enough to find it again, that's great. Love is a special circumstance. When you fall in love, a whole different set of principles apply. I think shallow relationships are boring. Who wants endless streams of shallow relationships? My relationships are very intense. Whether or not they last five years is totally beside the point. And I don't think my lifestyle is conducive to those kinds of relationships. I don't consider any of my relationships a failure. I think they have all been rather successful. But, boy, are they intense. Whoa, Jesus!

PLAYBOY: How many times have you been in love?

RONSTADT: It's really a little death, in a way, falling in love, because you surrender yourself. When you're about to fall in love, you have this inner dialog. You know, Is this guy really cool, is he thoughtful, has he shown me strength of character, do I love him? At some point, when you are really in love, you stop having this inner dialog and you just go on and love that person unconditionally and when you do, it's a little death. You surrender and you just totally let yourself open to that and it's the most vulnerable position to be in. But to me, it's the ultimate of sexual excitement to fall totally in love.

PLAYBOY: How many times has that happened to you?

RONSTADT: I went over that line only once. It was really frightening and it took me about two years to come back.

PLAYBOY: Was that with J. D. Souther?

RONSTADT: It doesn't matter. But once you totally let go, it is not easy to regain control. There is a part of you that always stays connected to that person and it changes you. But I still think it's neat. I still think it is something to strive for.

PLAYBOY: So you are not totally in love with anyone at the moment?

RONSTADT: That's right. I realized that that first time I actually went overboard. I went splat! It was such a wonderful feeling. That was stage one. Stage two was learning what the consequences are and stage three is being very careful. I don't think there is anything wrong with taking a real long time to fall over the edge the next time, because the next time, I would like to stay there. It's like reading your owner's manual. You read it, you do what it says and you do it pretty good.

PLAYBOY: Do you want to get married?

RONSTADT: As a life goal? Not really. I think it would be nice to have a mate whether it involved marriage or not. And I understand the reasons for wanting to ritualize the situation. It lends a bit more weight. But sometimes for people like me, who are real skittish and need a lot of freedom, maybe having that extra weight might be a burden. I've never seriously considered marrying anybody so far. But I've gotten some interesting proposals.

PLAYBOY: Do you want to have children?

RONSTADT: That's the big one. I've thought about it a lot, especially as I get nearer to 35. I like children a whole lot, but that's not a good enough reason. The only reason to have children is because you want them more than anything else and if I get to that point, I won't care if I'm married or not. I'd prefer to be with the kids' father, because I think that would multiply the enjoyment and the richness of the experience geometrically, but I don't think it would be impossible to do it alone.

PLAYBOY: Then you're not really looking for a permanent commitment.

RONSTADT: My favorite Brownism is: "Choice is the enemy of commitment." Here I am, cruising around the world, and you see this one and that one and it makes it hard if you're with one person. Suppose that person comes up short in a couple of areas and you miss that and you go to a city and find a person who's just got those two things and maybe none of the others and you go, "Why shouldn't I have that? I want that." It's just human nature.

PLAYBOY: Do you think monogamy is impossible?

RONSTADT: I don't think it's impossible; I don't think it is particularly necessary. If you live with a man and he is unfaithful to you, the only thing you can do is hope you don't find out, because it may not have any bearing on your relationship. Or if you are unfaithful to the man, I don't think you have an obligation to tell, because sometimes it is more destructive to tell. You should try real hard to stay true, though, because it's less complicated. You may be at a crossroads with somebody and if you just stayed with him, stuck it out a little bit longer, you may get up to the next level, which may be really wonderful. And if you get tempted astray, it may damage whatever kind of momentum you have going. But then, on the other hand, it may enrich it. Who knows? There just aren't any rules. I don't think a relationship can survive continual deceit and lies. As for occasional deceit and lies . . . (Laughs)

PLAYBOY: You are obviously a man's woman. Professional friendships aside, do you Like other women?

RONSTADT: I do like women. I am suspicious of people who categorically don't like men or women. Forget it. They have nothing to teach me. I can remember a time when I had very few women friends because I was on the road and everybody I knew was a man. I got into a bad habit of always being able to strike up a friendship with a guy based on being able to flirt. If all else failed, I could flirt with a man. I could bribe him into liking me. You can't do that with a girl. There is a whole other dynamic that is set up between two females and it can be sexual, but heterosexual, like in Julia. Women friends are important.

PLAYBOY: How difficult is it for a rock-'n'-roll star to have friends?

RONSTADT: We all work so hard out here that we isolate ourselves. It used to be, before we all had nice houses, that we all lived in crummy apartments and it was so depressing that we all went out to clubs every night. And the clubs provided a surrogate family. But then we all got record deals and money and big houses and that surrogate family changed. It, in a way, became the staff - you know, the people who help run your life - because our lives became so complicated with all the traveling. I don't have time for those little relationships that are important. I don't run out to the Troubadour every night. I have this nice house and I'm tired, so I slop down and watch TV. The success broke down something vital in the friendship process, as well as in the process of how we create music.

PLAYBOY: What do you mean?

RONSTADT: There was a time when I knew every single group or performer who came into town through the Troubadour. I knew every new trend in music so far before it was ever felt anywhere, because I was there when it was being formed. And, boy, it's real interesting, what's going on in the music industry right now. I know a lot of people are getting laid off and it will be harder for new acts to get deals, but it also means that in order to support themselves, groups are going to have to go back to the clubs. It's just going to get smaller. Those giant, expensive tours, with 30 people, four semis, stuff like that, just cost too much money. I think it will ultimately give the music a kick in the pants. I think pop music was commanding a disproportionate influence on culture and now it's getting back to normal. It will still be important, but pop music will now just take a seat, instead of driving the entire train. People may not have to live their lives vicariously through rock-'n'-roll stars. To me, that was real oppressive, because not everybody is supposed to be a musician.

PLAYBOY: Do you think this financial crisis in the music business will be good?

RONSTADT: Yes. The music will change and ultimately get better. We all got too greedy. It became an egotistical thing of saying how much money you got paid or how you just engineered a $1,000,000 deal and all the bragging about what you got written into your concert riders, like cases of champagne, Perrier, caviar.

PLAYBOY: Do you ask for tins of caviar in your concert contracts?

RONSTADT: Too many calories. No, I once had written in that I wanted a case of Shasta Diet Chocolate, and then I heard that some of the promoters were having a terrible time and going to a lot of expense to get it and I said, "Well, Tab is OK." But once, I saw these silk nightgowns I really wanted. They were so beautiful and so expensive. It was time to resign with my record company and I considered asking the company to buy them. But why should it? They aren't necessary and have nothing to do with the music. I thought, Well, if I want them, I'll just buy them myself.

PLAYBOY:Does what you've been saying mean you'll go back to playing clubs?

RONSTADT: I think the club scene will get real healthy again and it will give some acts places to play. But there are some practical reasons why it would be hard for me to play clubs like the Roxy and it's not because I've gotten lazy or selfish. For what I would be paid to play a club, I couldn't pay one member of my band a week's salary. The way costs have escalated and the particular economic sandwich I am in right now, I can't afford it - at least not all the time. But I plan to play the Palomino and do odd clubs during the tour. I need the feedback.

PLAYBOY: Why weren't you involved in the benefits opposed to nuclear power?

RONSTADT: I didn't have a band and I felt it might be construed as an attempt on my part to start stumping for Jerry Brown.

PLAYBOY: What's wrong with that?

RONSTADT: I feel it can be dangerous for me as an artist to get involved with issues and, particularly, with candidates. But at some point, I feel like I can't not take a stand. I think of pre-Hitler Germany, when it was fashionable for the Berliners not to get involved with politics and, meantime, this horrible man took power. But it is difficult for me as a public person. I don't want people to take my word for something because they like my music. That's a danger in itself. I am real aware of my ability to influence impressionable people and I am reluctant to wield that power. If I am saying things about nuclear power, I want people to go out and learn about it. I don't want them to say "No nukes" because Jackson (Browne) and Linda say it. I don't want them to think that to be hip, they have to be a no-nukes person. I don't want people to think about issues when they hear my music. I really want them to hook their dreams onto what I am singing. When I'm out in public, I want to be singing.

PLAYBOY: But you are stumping for Brown. You had a $1000-a-couple dinner for him and you're doing concerts, something you said you'd never do.

RONSTADT: You know how most people burn their bridges behind them? Well, I have a tendency to burn my bridges ahead of me. I swore up and down I wouldn't do a benefit for Jerry. The artistic reason is the selfish reason, but also, I always thought that if I did a concert for Jerry, it would be perceived by the public as him trying to use me. They would say, "I told you all along: The basis of their relationship is that she can do concerts for him and make him a lot of money." But there is no way for me to stay neutral. If I won't support him, and I know him best, it looks like an attack. I would like him to be able to speak his ideas. I think they are really important and good and, for the most part, he's right. It's so hard for me, not only as a public figure but also as someone who believes in him, cares about him, is close to him and is on his side. I want to be on his side.

PLAYBOY: What's the reaction to your limited public support of Brown?

RONSTADT: I'm going to take a lot of heat for it, but I'm ready. I just don't feel that any of the alternatives are as good as Jerry, and that's what it comes down to. Look at it this way: The Eagles and I, in a way, represent the antinudear concern. Westinghouse is heavily invested in nuclear power. A candidate like Ronald Reagan can go to Westinghouse and ask for lots of money and despite the $1000 limit, Westinghouse can commandeer huge sums of money. Plus, it can hire lawyers and take out huge ads in the newspapers and continue to brainwash the American public about the safety of nuclear power, which I think is a lie. Jerry Brown can't go to Westinghouse. He can only go to the individuals. He has no corporate financing for his ideology. A candidate like Jerry Brown can't go to Arco for money for solar power, because it's not in the company's interest. I believe it's in the public interest to have a candidate who is interested in furthering technology like solar power and protecting us from things like nuclear power.

PLAYBOY: Then you're not wary about ill-informed performers' affecting politics.

RONSTADT: A lot of us were naive in the beginning about doing benefits. We tended just to take people's word for things. I don't now. I read newspapers, periodicals. I'm not saying I'm an expert, but I am a hell of a lot better informed than before and better informed than the average person. I think my opinion is informed enough to put out there. Richard Reeves wrote sarcastically about how nobody would pay $400,000 an hour to watch him type, but Richard Reeves, in fact, swings much more influence with a typewriter than I ever could. He's a political writer. He sways public opinion every day. Doing a concert for a candidate can't swing an election. We flatter ourselves to think that. What I can do is provide better access to the public forum, and then it's up to the public to decide. Artists like Jane Fonda, Joan Baez, Vanessa Redgrave, I say more power to them, they are sticking out their necks. I don't particularly want to stick out my neck. But I don't see how I can not take a stand. It's dangerous territory for me, that's for sure. But if Frank Sinatra is going to do a benefit for Reagan, then I guess I have to do a benefit for Jerry.

PLAYBOY: Let's return to your music. Where do your songs come from?

RONSTADT: Mostly, I get them from my friends. And from those situations late at night when a bunch of people have gotten together and gone through a lot of social ritual and the defenses are down and you get real bored. The best cure for boredom is music, and that's when the ideas start coming and your fingers start to ache and you start harmonizing, and then someone says, "I just wrote a tune," and you take the plunge. I keep getting all these funny demos from housewives and I keep praying one of those songs is going to be brilliant. It never is.

PLAYBOY: Have you ever sung anything you felt was perfect?

RONSTADT: I sang Sorrow Lives Here in Tokyo once and I thought it was perfect. I got this reading on this one line exactly the way I wanted to do it. I remember that night.

PLAYBOY: Is there one song you never get sick of singing?